Part 5 of “Who Will Do The Work Of Upgrading America’s Infrastructure?”: Recruiting and building a highly-effective CTE teaching staff; and the profile of a successful CTE high school student and graduate; both are reflections and manifestations of the school’s philosophy of CTE education.

Successfully recruiting and developing a highly-effective CTE teaching staff. Start with a strong strategic professional development plan in mind.

One of the critical components of a successful CTE high school program or school is the expanded commitment that must be invested in instructional coaching. In almost every situation, a CTE program/school will need (depending on its size) to employ a few or many non-traditional teachers. These teachers may have spent a previous work life in a particular career field or industry (e.g., plumbing, carpentry, nursing, EMT tech., etc.). However, the best CTE teachers to recruit are those presently or who have taught in the past, in a skills trade apprenticeship or professional preparation program (they will at least have some “teaching experience” upon which to build on).

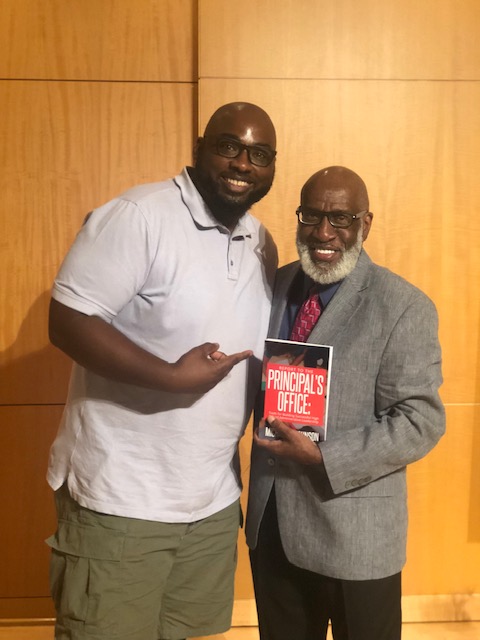

But the school must still craft a comprehensive pre-teaching assignment training and ongoing professional development plan for these teachers. This is particularly true since teaching in a post-high school adult program is very different from teaching teenagers in a high school. I understand a popular US notion that is held by many outside of professional education, is that anybody can teach. For sure, the myth that anybody can teach (or be a principal, superintendent…) has done great harm to the profession and even greater damage to our most vulnerable students. Teaching is a complex and challenging craft, even for those “new teachers” who have graduated from a conventional 4-year undergraduate teacher education program. Obviously, the long-term and sensible plan for the development of “non-traditional” CTE teachers is to provide ongoing professional development that covers (in a condensed and concentrated way); many of the fundamental knowledge and skills of a professionally trained, “certified track” teacher, such as lesson planning, instructional (delivery) practices, questioning techniques, developmental psychology, pacing, classroom management, executing during-the-lesson and post-lesson student assessments, etc. This intense pre-appointment professional development must continue throughout the first few years of teaching, in-school, after school, and on weekends to the greatest extent possible, mirroring the essential course offerings found in traditional teacher education programs. This formal teacher training must be combined with (depending on the size of a CTE program) a dedicated Teacher Instructional Support & Resource Center with an F/T (dedicated to the CTE teachers) instructional coach. Ideally, these “uncertified” CTE teachers can earn official teacher certification if the project is done in partnership with a local college that offers an “on-school-site” teacher education program in partnership with a district. Perhaps the “financial-tutorial-agreement” between the seeking to be certified CTE teacher and the district could be something like: For every tuition subsidized year the CTE teacher spends in the joint district/college teacher education program, they must, in turn, commit to work in the district/school for a year or repay the tuition. And “super-ideally” in a proactive way it would be very helpful for public education for colleges to set up a 4-year teacher education program specifically focused on producing a teacher certification program for (STEM and) non-traditional CTE teachers! But in the present and immediate future, CTE schools more than likely will need to recruit CTE teachers who have no prior training in K-12 pedagogy or instructional methodology. And so, the school must set up an “in-house” concentrated professional development series of “mini-courses” if these teachers are to be successful. These courses should start over the summer before the fall semester of their teaching assignments. The prospective CTE teachers will need to be paid (another necessary program cost) for attending the “for credit” summer teacher training institute. And it would be beneficial for those prospective CTE teachers to earn college credit toward an undergraduate education degree during their summer months of classes.

A little later, I will discuss the best approaches to finding and recruiting these teachers, which is not separate from the school’s overall philosophical thinking about how the principal operationally should effectively manage a CTE program, department, or school. But first, as things should proceed (but often does not) in public education, the learning needs of CTE students should frame (dictate, define and determine) the skills and knowledge capabilities required of their CTE teachers.

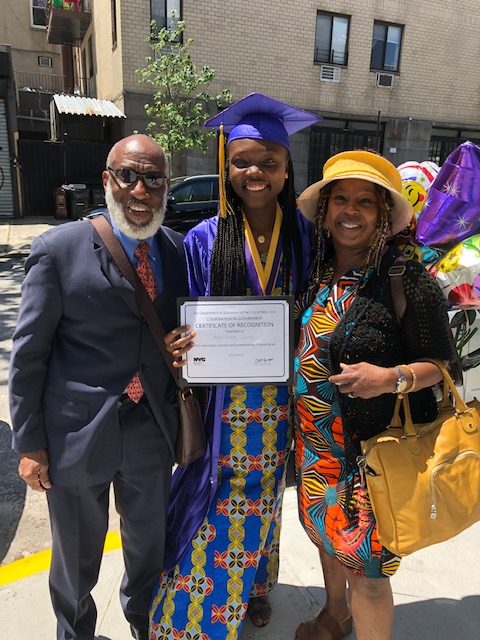

The profile of a successful CTE high school student and graduate reflects and manifests the school’s philosophy of CTE education. With high school CTE programs, we can, academically and operationally, both bake “bread” and contemplate the artistic and poetic beauty of “roses,” which is why it’s essential to integrate CTE courses and the school’s other rigorous and enlightening academic offerings to create a “dual-diploma” graduating CTE student.

As with any effective high school academic department, the place to begin the forming of an overarching departmental philosophy, standards, objectives, structure, staffing needs, and operational strategies is to ask this critically essential question: “What are the explanatory competencies and characteristics (rubrics) that describe and define a graduate of our CTE department?” You cannot separate teaching and learning and organizational practices from programmatic and student achievement objectives/outcomes; pedagogically speaking, there is an “equal-sign” situated between and links program function/structure and program end-products/production. Therefore, for that student who completes a four-year CTE major program, the following brief bulleted outlines describes the primary programmatic and student conceptual and behavioral objectives that should be (necessarily) jointly realized in a four year CTE program or school:

• All CTE students must take and pass a first (ninth grade) full year CTE rotational survey of CTE “majors” class. The rationale and purposes of this class is to allow students to become familiar with a wide spectrum of CTE areas of study, and ultimately careers. Students were surprised at PHELPSACE* (a STEM-CTE school I designed) that during the ninth grade CTE survey class they discovered an unknown passion for a heretofore not-very-interested-in or not aware of an interest in CTE course of study. Anyone who has spent any considerable amount of professional or parenting time with teenagers, will know that they will often announce (demonstrably) that they “don’t like” something until they “do like” that something; that is, after being exposed and experiencing it! Thus, one of the teaching and career guidance objectives of the CTE survey class (and schooling in general) is to help students to clarify, sharpen and expand the perimeters of their “like” perceptions. The CTE survey class also offers students a “time and transcript-safe” chance to re-select their area of intended CTE concentration that was stated on their 9th-grade application and in their admissions interview (Yes, applying CTE students must be interviewed; the programs are educationally fulfilling and wonderfully engaging, but many of these programs carry a higher degree of potential safety-danger; and therefore, you must “lay eyes and ears on” every prospective CTE student to ascertain their level of attitudinal commitment and safe behavior discipline and comportment capabilities). The CTE survey class also offers students the chance to see the interaction and inter-relatedness of seemingly different CTE “specialties” and careers. For example, how a building, a bridge, tunnels or any other structure is built by applying multiple skilled tradespersons (practice officially utilizing school-wide, the term: “tradesperson” rather than the commonly used “tradesman”). It also gives students the opportunity to think about combining two presently existing career objectives, e.g., construction trade + engineering = construction (civil) engineering, creating a completely new job description, or pursuing an entrepreneurial opportunity. A ninth grade, one-year CTE survey class will allow students to rotate and take an introductory class in each of the CTE content specialty areas (electrical, masonry, plumbing etc.) of the CTE program. Based on this one-year experience, at the end of the year students will be asked to select a CTE “major-concentration” path of study. This survey class can take place in a normal forty-five minute class period, and the credit earned in this class will go toward satisfying the CTE graduation “diploma” requirements. This will of course add an additional class to every ninth-grader’s schedule (one of many reasons a longer school day is required). The only exception would be the engineering CTE sequence; this should start in the ninth grade, preferably with students who have taken algebra 1 in the eighth grade or algebra 1 in the high school’s pre-school year Summer Bridge Program. The reason is that high school students seeking to be admitted to an undergraduate engineering program should have taken calculus (and physics) no later than the twelfth grade (you don’t want students to encounter that first year daunting engineering major college course: “calculus for engineers” without having a high school calculus course “under-their-belt.”). Also, the pre-engineer college sequence will take the full four years of high school study because it covers a diverse syllabus objectives of the student learning about and experiencing many engineering specialties (e.g., civil, mechanical, chemical, electrical, traffic/transportation, etc.)

Back to the general CTE survey/rotation classes, which can last anywhere from two days to 2 weeks per career area, based on the information and skills requirements for that study topic ( e.g., drafting, CAD/CAM will take a couple of weeks of syllabus time). The CTE course should include a broad spectrum of presenters from specialty areas within that CTE career category. For example, carpenters who make furniture and those who work in building construction. Or masons who work on general housing-related structures like retaining walls and paved walkways, and stonemasons who do historical building restoration. The key here is to expose students to CTE careers they may not even know exist (e.g., theater: set design, construction, sound, lighting, and costume design). In this way, the students can be exposed to the full diversity of job categories in a wide spectrum of CTE fields. All of these ninth-grade introductory classes can be co-taught utilizing a skilled (working or retired) practitioner in the particular CTE job-category along with a traditionally licensed teacher or paraprofessional working in the CTE department; or, the “introductory survey classes” could be part of a school-building assigned CTE teacher’s course assignments if there is room in their schedules. All outside-of-the-school visiting instructors should receive a brief orientation to familiarize them with the school’s practices/procedures, rules, and regulations that govern public school education (all should have a “co-teaching” certified teacher or a very good and experienced paraprofessional in the room at all times).

Outside of school, trips to actual CTE work-sites are a necessity. Therefore, the success of this survey class also depends on the school/CTE department building strong outside-of-the-school collaborative partnerships with the organizations and trade/professional unions and associations that will supply the “teaching venues” and volunteer teachers. Although these professional expert presenters are volunteering their time, the school community should appreciate the tremendous donated sacrifice and cost these individual’s companies and governmental agencies are making by providing their paid employees time off to teach on-sight or at a public school.

As you seek to raise the necessary extra-funding for a CTE program or school, there is something you should know principal, and that is the vast majority of governmental and non-governmental organizations/institutions, their executives and employees, actually want to see public schools succeed; the “brake-down” in the “relationship” is on the public school end because after acquiring massive amounts of tax money from individuals and businesses, we continue to send so many “half or poorly prepared” high schoolers into the adult world of work or unemployment (the exception, of course, would be the Criminal Justice Industry, which benefits greatly from, and is sustained by, our ineffectual practices). For example, one large electrical firm in partnership with PHELPSACE donated a professional master electrician full-time to teach our sophomore-senior electricity courses for an entire school year; which saved me the cost of a whole teaching position, and the fact that he was an African-American male in a school that was 90%+ Black American was an added inspirational plus! This brings me to my next point: Although it is not a qualifying criterion for the success of the CTE survey course, if, at all possible, the school and CTE department should “hint carefully” that diversity of professionals (e.g., presenters of color and women) would be greatly “value-added” appreciated; but the “who” these presenters are should not be a “deal-breaker” after all their services are free to the school; but it has been my experience that all of the “sending volunteers” organizations, trade unions, professional associations, and institutions have all been sensitive and positively responded to our “representation and diversity” learning objective concerns.

Finally, in the construction trades sections of the CTE survey class, many girls will discover how talented and gifted they are in areas often identified as “male careers” (and their male peers will also learn how skillfully good these young ladies are and will begin to “put-some-respect” on their names!). I have seen girls excel in areas like welding (see the picture of the young lady top welder-of-the-class on this blog page’s platform), masonry, carpentry, plumbing, etc., in sections of the yearlong CTE survey class and then continue to excel as they move into the concentration phases of their sophomore-senior school years CTE “major” studies. The principal, CTE director, and AP of guidance must be ever vigilant in making sure that girls are unconsciously (and perhaps not maliciously) excluded, “self-exclude,” or discouraged from pursuing a construction skills trades career pathway. Making the CTE work-study space “gender-neutral” (same standards and expectations for all students) is a necessary volunteer and CTE staff orientation and departmental meeting conversation since many of the male survey class volunteer instructors and even the school-based full-time CTE construction trades/mechanics faculty members may not have extensive (or in some cases any) experience of either teaching/training or working in the profession with women.

• There must be a link between program “student profile” objectives, program functionality, and the physical structure of the instructional spaces. For example, if a district is building a brand-new CTE high school or refurbishing an existing school building (e.g., PHELPSACE), the investment must be made to make the architecture and construction of the building itself a significant part of the CTE teaching curriculum and that would include putting the school in a position to pursue and achieve the ultimate LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) platinum status.

• There is a required dual-certification graduation goal (a high school rigorous academic diploma & the appropriate CTE certification), which will mean that the student has met all of the academic requirements for gaining admission to either a two-year or four-year college. All CTE students should apply to a college program (perhaps closely related to their CTE major); the school should cover all application fees, even if they don’t plan to attend college or have decided to delay college attendance for some date in the future. It’s always better (and some former “reluctant” CTE students thanked me for “pushing” this mandate years after they graduated) for a student to have a 2 or 4 year college acceptance letter “in-their-pocket” and then communicate to the college that they are delaying the start of their college studies for a post-high school work-study CTE program (e.g., a construction trade apprenticeship school); then to “scramble” 1-2 years after their high school graduation to acquire (a now more difficult) admission to a college.

• A CTE student must be emotionally disciplined, highly organized, and “highly-efficient” academically. The school’s CTE four-year course of study follows a prerequisite (required classes) and cohort-track format. Ninth graders, in particular, generally face that “standard” challenge of mastering the organizational skills to navigate any high school academic program successfully; CTE programs will present additional challenges for those ninth-graders who are in pursuit of dual-diploma graduation status. High schools too often assume wrongly (or under assume) the degree of “mental-preparedness,” and the required high school culture “soft skills” awareness capabilities of ninth graders. The CTE program must set aside some time (possibly the first week of the 9th grade school year) in the CTE survey class to teach students organization skills “best practices,” productive study techniques, general (all subject areas) study prioritization/optimization skills; test-taking skills, how to manage short and long-term projects and assignments, and academic time management; or these students are going to struggle (and perhaps fail) in a high school CTE program; a sequence of study that is highly rewarding, but leaves little room for course failures, especially in the case of CTE courses where there is most likely no summer school make up classes.

• Students should be exposed to the many different CTE employment “promotional” skill levels, “soft” and “hard” skills and knowledge requirements (e.g., “trainee,” “extern-intern,” certified, “mastery,” and supervisory/managerial job categories in a given industry or trade. And also, be exposed to the numerous present and possible future “sub-specialties” inside various CTE professions (e.g., underwater welding and robotics, nurse anesthetist, electric cars maintenance, etc.)

• The CTE program must utilize the (costly) actual tools and equipment used by professionals working in the CTE field they are studying; and where that is a challenge (e.g., heavy construction vehicles and equipment), field trips and computer simulation technology should be employed.

• A senior CTE project should always be required (and evaluated) in any CTE program. For example, a creative performance/art work, culinary presentation (with invited professional chefs and food critics), original fashion designs, architectural “green building” design, or engineering innovation service projects. Or, the students could do a group/team senior-year CTE project across multiple (4 is the best working and assessment number) different CTE major areas of concentration, like designing and building a school campus greenhouse.

• Students should successfully pass the CTE major certification exams (e.g., CISCO), end-of-course assessments, written and practicum qualifying exams for admission to a CTE post-high school training program, and/or a specific construction trades apprenticeship school.

• Outside of class, program, and school enrichments. Optimally, a CTE student will be able to spend at least one school-semester, or during the summer, in an applied project mentorship program, on-site extern or intern-ship, work-study experience, a summer job connected to that student’s CTE area of concentration. (In cooperation with a wise city administration, the SYEP program could be integrated into this objective).

In addition, CTE students (in developing their portfolios) should engage in a CTE career-related school team or club. For example, for the pre-engineering students NSBEjr and/or the FIRST Robotics team; for CISCO or Microsoft certification students, the Cyber Forensics-Security Competition Team. In that CTE course of study where there is no national high school club, association, or competition, the school should create an in-school or inter-school expression of competitions, clubs, or junior professional associations.

• Students will be proficient in thinking and linking CTE “conceptual” and “behavioral” skills competencies. The CTE program’s instructional model will challenge, but ultimately empower students to be equally proficient in theoretical and performance-based learning. There is no learning they engage in that is not connected to practice and no practice disconnected from the theoretical learning they study. The CTE department is essentially the praxis heart (reflective model) and the practiced art (creative example) of the entire school’s pedagogical commitment to a Project-Based-Learning-Approach for schooling generally, and operationally for teaching and learning in all academic areas.

• All CTE students must complete (a CTE diploma requirement) some community/school service project before graduation, for example, serving as an assistant coach for a middle school robotics team; technical support for the drama club, a mentor for ninth graders joining the computer club, membership on the school’s LEED team; beautifying, upgrading, renovating, and restoring parts of the school building and the school building grounds, etc.

• All CTE students must build a 4-years in the making, electronic and paper senior portfolio (expanded CV/resume). Including information highlighting the student’s participation in both CTE and non-CTE school activities, programs, or teams. This senior portfolio should reflect the intellectual and skills capacity of a “well-rounded” student. Don’t be shy about building a dynamic “CTE-PR Package” (senior portfolio) for students; after all, the best high school athletic programs do it all of the time!

• The model CTE student will be thoroughly grounded in non-STEM-CTE subject areas such as fictional literature, poetry, history, plays and essays, creative design, and performance arts. (again, for reasons to create a “rich senior portfolio profile”). In other words, a “well-rounded” and rigorous-rich transcript. In addition, given the financial resources, schools should offer “CTE/Liberal Arts” elective courses, e.g., “computer-generated art,” “history of technology,” “archeology and architecture,” and “biomedical engineering.”

• Work force-place-site experiential knowledge. Over four years, the school’s CTE graduates would have participated in many individually assigned or school-sponsored/organized CTE careers-related trips. “School Trips” as a learning tool have fallen out of favor (especially in high schools). But with good school leadership organization, this teaching and learning vehicle can be of tremendous academic achievement and career enlightenment value, particularly for those students who don’t have the opportunity to interact with a diverse spectrum of successful professionals and have access to informal education institutions.

• CTE graduates will be well informed and well-rehearsed in resume writing/job interview standards and techniques. The CTE department will also familiarize students with the professional work environment “soft skills” and “cultural-linguistic code-switching” skills required to succeed in an internship or future employment setting. The CTE departmental objective is to have the student psychologically and attitudinally “job-ready” by graduation.

• (And here is where the Entrepreneurial Principal must show up) All CTE construction skills (and some other CTE programs, e.g., EMT,) trades students should receive a complete set of personal, professional tools (from the culinary arts to carpentry) upon graduation.

High School Career Technical Education (CTE) allows us to move away from disempowering dueling diplomas and move into empowering dual diplomas.

In closing, it is unfortunate that too often in public education, in too many ways, and with too many students, we fail to establish a positive, adaptive, and valuable after graduation path for students to achieve short-term motivational career accessibility and long-term societal financial sustainability. The high School CTE dual-diploma graduation objectives allow us (starting in the 9th grade) the opportunity to provide ourselves and students with a 4-year end-of-process plan that equips young people with the knowledge and skills to confidently take the next step in the adulthood and career maturation process. Even if a student chooses at the end of 4-years of high school to delay or completely abandon a CTE career option, it will not hurt their chances of utilizing the CTE skills they learned in other career endeavors; and it surely won’t hurt their resumes since they will have the profile-resume advantage of being a highly-effective dual diploma achiever. And besides, if public schools provided their CTE graduates with more and not less post-high school graduation options to choose from, then that is a “problem” that our nation and our children are in dire need of having.

*Phelps Architecture, Construction, and Engineering High School, DCPS, Washington DC.