I do hope that one of those schools will be a STEM-Applied Computer Science CTE SHS!(1)

For many of us veteran Title-1 (poor) schools urban (and rural) professional educators, the questions have never been about our student’s intellectual abilities, their passionate aspirations, or the hopes and dreams of their parents and communities. Instead, it has always been about expanding and extending the empowering exposure of high-quality teaching-learning experiences, “good atmospheric” and enriched resources conditions to larger cohorts of very capable students. This means those students have the opportunity to enter a clean, calm, and productive school environment; having access to adequate health, social-emotional, and counseling services; their teachers have the appropriate equipment, learning-support resources, and supplies, and the school follows a curricular approach that is rich in rigor, and strategically undergirded and guided by a team of skilled efficacious adults, inspired by a love of unconditional high expectations.

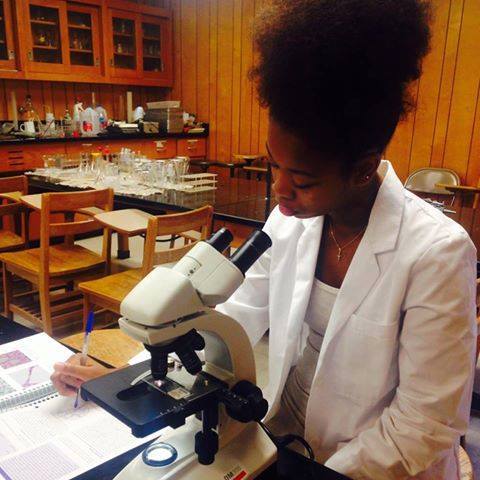

Young people have the amazing ability to rise and meet the academic challenges presented to them, often even shocking themselves when they perform at an exceedingly high level. But this can only happen if they are given a chance and learning conditions that will allow them to demonstrate the full range of their innate repertoire of skills, gifts, talents, and one or more expressions of the “multiple intelligences” (e.g., logical-mathematical, musical, physical, interpersonal, creativity, etc.) they possess.

This is why as a former NYC superintendent (CSD29Q), I “broke” the rules and decided on my own to dramatically expand the district’s limited Gifted & Talented (G&T) classroom “allocations,” including adding some of our “underperforming schools” to the list! And, of course, some of the folks who were centrally “in charge” of G&T programs were very upset with me (“turf-protectionism” is a big deal in school-district bureaucracies and can often take precedence over students’ needs); however, the then NYC Chancellor (Harold Levy) wonderfully supported my decision. That decision “paid” for itself by raising the standardized exams proficiency levels of all students, at all proficiency-performance levels, in every newly minted G&T school! You see, (something else the present mayor got right) the mere presence of elementary and middle school G&T classes (like high school I.B., A.P., exciting advanced electives, academic teams, and programs) will cause an entire school to “think-of-itself” and be seen by prospective parents more differently and positively! This is why as a CSD29Q superintendent, I saw a dramatic drop in parent requests for transfers or the parent’s use of “unofficial transfer” methods when I placed a G&T program along with an exciting applied STEM lab in a so-called “underperforming” school building.

But it should also be understood that the unfortunate and imprecise term “underperforming school” can be misleading since in every school, regardless of a school’s lackluster academic performance data, you should know that there are cohorts of students in that school building who are, in fact, performing well and in some cases “overperforming” and so, what are we to do with those children? (There are a lot of students who are actually “underperforming” in so-called “good” or “high-performing” schools, but that’s a topic for another day).

We should stop defining and dismissing students’ naturally high and perhaps undiscovered capabilities based on the neighborhoods where they live, their family’s income, their racial or ethnic identity, their parent’s level of education, or mastery of the english language.

I don’t believe that whoever is “in transcendent charge” of distributing talents to newborns is using any of the abovementioned socio-economic criteria (all out of the child’s control) as a determining factor of who does or does not get a talented gift(s) at birth. And suppose you don’t believe that all children are provided at birth with a special and unique contribution to the world. In that case, I don’t know what to tell you, except that I just hope you are not working or plan to work in the education field!

The mayor has also suggested that the new Specialized High Schools (SHS) admissions process will utilize a more comprehensive inclusionary focused approach rather than an exclusionary focused admissions process. This could mean assessing the multiple modalities (e.g., visual, verbal, touch, hearing, etc.) by which children learn and express that learning. This opens the SHS admissions opportunity door to a much wider pool of students than is allowed with the present SHSAT(2) process; this will further provide NYCDOE educators with a tool to ‘discover’ those young people who are not great at or who are ‘naturally nervous’ test-takers. These “challenged-test-takers” under new and improved screening procedures would be able to demonstrate their high levels of skills and knowledge outside of a “high stakes,” win/lose, one-day, one-chance exam. But that won’t stop those critics who are opposed to any form of standards of assessment from engaging in soapbox sophistry; that is, of course, unless they are talking about the standardized assessments that have enriched their own (or their children’s) personal and professional lives like the: SHSAT, NYS Regents Exams, Advance Placement Exams, SAT, ACT, GRE, PRAXIS, LSAT, MCAT, etc.

Create more successful outcomes on the back-end by creating more opportunities on the front-end.

I believe this expansion of SHS sites in NYC could save a lot of young folks if organized in a strategically smart way. These students will gain access to a high school experience that will push them to their best academically performing selves and raise their competitive academic capacities. Too often, many on or above grade and performance level young people in Title-1 high schools are fighting on two learning-fronts; first, trying to master the academic material and secondly, trying to navigate the very common learning distractions occurring in their schools and classrooms; this is too much to ask of an adolescent.

We need to absolutely improve the quality of education in all high schools in the city and, at the same time, allow academically advanced (especially those who are traditionally disregarded) students to demonstrate and perform in a high-expectations, peer-challenged, less stressful, and “safe-to-be-smart” learning environment. This work must be done as public school systems simultaneously improve (equalize) the quality (and quantity of that quality) of pre-high school learning in all elementary and middle schools. A student’s high school “opportunity-options” (e.g., advance, elective, AP courses, etc.) are ultimately determined and/or significantly influenced in their PreK-8 learning years, thus limiting or expanding their post-high school range of possible choices. Transitioning to a public high school should not be a quality learning survival-obstacle course, especially for children forced to cross an inferior pre-high school learning-less minefield.

(My warning to Eric Adams) The political pushback on this SHS initiative could get ugly and loud.

One of the argumentative attacks will be (and this is solely applied to high performing Black and Latino students): “If you don’t immediately ‘fix’ the entire system (or school), then no (Black & Latino) students should experience an educational program that meets their learning proficiency level needs.” And so, welcome to the club Mr. Mayor, for I have been on the receiving end of this kind of racially selective call for group mediocrity and collective underachievement thinking for many years; this line unfairly paints a lot of children in public education as “deficient learners” when they are not; it just could be that they, unfortunately, live in the “wrong” low-expectations/low-quality learning zip code.

One of the main reasons we in public education don’t do a better job with all children, including those struggling academically, is that we have not even figured out systemically how to do a good job with Black and Latino children who are on or above grade and performance levels; especially our Black and Latino boys who are members of that “on and above” group.

I challenge any leader or public education stakeholder to speak (as I have) at a state youth correctional facility; you will probably share the same alarming and sad thoughts I had as I drove home on that day:

“My goodness, those are smart and talented kids; how on earth did we fail them so badly!”

Unfortunately, specific segments of the US population send large numbers of their very capable, creative, inventive, and intellectually talented kids into the prison system; this is where they do successfully learn to apply their talents in the most personally destructive and societally harmful ways possible. We need to offer these young people (and ourselves) a more promising and positively productive future.

Mr. mayor, there will be push-back-hell to pay! (or maybe a ‘critical-mass’ of NYC parents will rise up and make their hopes and dreams for their children known!)

Interestingly, I’ve found, as an educator doing this: “equality of quality learning” work over the years, that the vast majority of these politically correct “push-backers” (yes, it purposely rhymes with bushwhackers) on anything relating to Black and Latino students receiving any type of “academically advanced” learning will be people who either themselves and/or their children enjoyed, or are enjoying some kind of public or private “specialized enriching educational exposure” — It’s a cynical attitude of: “what’s good for thee (the masses) is not good for me (the entitled ‘leader’ of the masses)!”

But I say push forward Mr. Mayor, because, if this works, many NYC children will win, meaning they will at least have a better chance at having a decent and rewarding post-high school life. And ultimately, regardless of the cost, we must always be in the saving the children “business” and not in the business of supporting adults who want to create hypocritical PC hashtags or who want to pontificate on news and social media platforms, where they engage in meaningless and simplistic soliloquies that have nothing to do with real students in real public schools.

The public high school experience is our last chance in the PreK-12 system to make a significant and lasting difference in a young person’s life; let’s take every opportunity to make that difference powerfully impactful!

(1) See: REPORT TO THE PRINCIPAL’S OFFICE: Tools for Building Successful High School Administrative Leadership; Chapter 16 on establishing: “An Effective Career Technical Education (CTE) Program”; and Chap. 18 on; “Building the model schoolwide technology program and department”… https://reporttotheprincipalsoffice.net/about-the-report-to-the-principals-office-book/

(2) SHSAT: Specialized High School Aptitude Test presently in use for screening students admissions to gain access to several (but not all) of NYC’s specialized high schools.